THE ISSUE

In this post I tackle the issue of the history behind the text. So the particular example given by Christoph focuses on the issue of obedience language and whether this indicates that the addressees of the letter had been undergoing persecution,

If we still want to talk about whether the persecution- or the no-persecution hypothesis is more probably in light of the evidence, e.g., in light of the fact that there is said obedience-language, we can raise the possibility that the likelihood factor and the prior probability might be easier to assess. And as I argued, at least with respect to the prior probability a good case can be made in light of James Corke-Webster’s research.

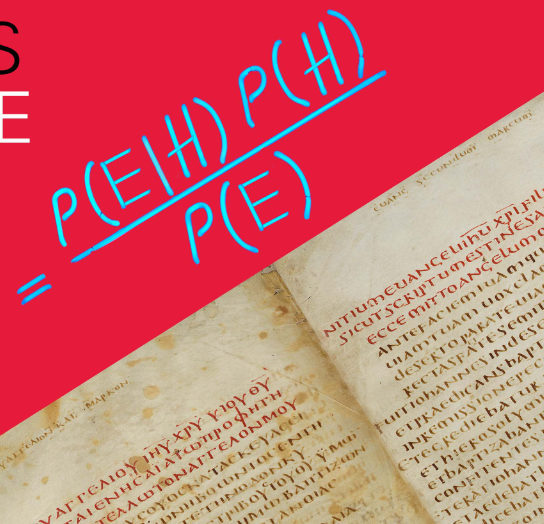

So, the question is do we need Bayes to find this, or can we go to Pr(H|E) more directly? What is the probability that there was persecution assuming that there is obedience language? Well, initial impressions aren’t good. We, or at least I, don’t have any initial idea what this might be. Why this is we’ll get into later. So, how does Bayes fare? In order to find this we need Pr(H), Pr(E) (or a way to calculate it), and Pr(E|H).

Pr(H)

Christoph mentions that James Corke-Webster’s work can give us a good handle on what the odds of persecution of a minority group in the Roman Empire. Keep in mind, as I discussed in part 2, that we don’t necessarily need exhaustive knowledge in order to come to Pr(H). We can research a sub-sample and if we have good reasons to believe it will generalize, we can use this to group our Pr(H) assessment. As I haven’t read Corke-Webster, I’ll just assume that is what is going on here.

Pr(E)

Now I’m not entirely sure how ‘obedience-language’ is to be specified here, but it seems reasonable that it can be rendered precise enough to be evaluated reliably. Assuming this is true we can run through the databases of ancient literature we have and come to an understanding of E and most likely Pr(E). So, this does not seem to be an issue either.

Pr(E|H)

This refers to the probability that we find E (obedience language), assuming that H is true (there was persecution). Now how are we to find this? While we might have intuitions it certainly doesn’t seem obvious. Christoph flags precisely this problem and wonders,

Something that I am still not that sure about is whether the problems that impede our direct access to posteriors also automatically negatively influence our ability to estimate likelihoods.

This is a great question and the answer to it is—sometimes. When we look at the nature of conditional probabilities we’ll see why. The two conditional probabilities we’re looking at are Pr(H|E) and Pr(E|H).

As you can see, the numerator for both of these is Pr(H∩E). So anytime we cannot determine H∩E we are going to have a problem with both the ‘likelihood’ and the ‘posterior’ probabilities. In our test case we need to know the places where there is both obedience language and there was persecution.

As I mentioned earlier, our (or at least my) intuitive response to the question ‘What is the probability that there was persecution assuming that there is obedience language?’ is a blank stare. The reason for this wasn’t so much that we have no grasp on obedience language, Pr(E), but that we don’t have a good grasp on where obedience language and persecution are found together, Pr(H∩E). To discover Pr(H∩E) we would need to have knowledge about the historical realities on the ground and this is often the very thing that we don’t know (and are often trying to indirectly infer from the text). Since finding Pr(H∩E) is the problem here, and this is required for both Pr(E|H) and Pr(H|E), then the answer to Christoph’s question in this case is yes. What impedes us from directly finding Pr(H|E) also impedes us from finding Pr(E|H).

Related Issues

The case where this is not a problem is when the problem with finding Pr(H|E) comes from a lack of access to the denominator, Pr(E). Since Pr(E) does not figure in Pr(E|H) then its lack cannot be a problem.

Now from a Bayesian standpoint, we will still need to find Pr(E). In cases where we do not directly know it, then (as we saw in part 2), the standard way of dealing with this comes from the fact that Pr(E) = Pr(E|H) Pr(H) + Pr(E|~H) Pr(~H). We already have Pr(E|H) and Pr(H), so all that is left to find is Pr(E|~H). After finding this, then ta-da, we can plug everything into Bayes and calculate.

Note, however, that we can also just plug this into conditional definition of Pr(H|E) and calculate. This makes sense because all these formulas are consistent and derivable from each other.

Final Thoughts

This leaves us with the question of what advantage is there to the Bayesian movement from ‘prior’ to ‘posterior’ when mathematically one can calculate things in multiple different ways. The answer, I think, depends on context. If you look at how Bayes is actually used in different areas, there are different justifications / benefits of retaining priors. So the reason for Bayesian inference in Bayesian statistics is different than it is for Bayesian epistemology which is also different than it is for Bayesian confirmation. I think I’m on-board for Bayesian stats (on at least one way of viewing it), sympathetic with Bayesian epistemology, and rather unconvinced by the need for Bayes (i.e. always reasoning from ‘prior’ to ‘posterior’) in confirmation. However, cashing this out would be the task of a different blog series.